That hidden system runs on numbers, the IP addresses. Without those numbers, nothing would know where to go. You could type in a website name, but the request would simply vanish because there would be no unique address for the server or for your device.

These addresses cannot just be thrown around without order. If two devices had the same one, messages would be lost, just like two houses with the same street number would confuse the mail carrier. So, long ago, groups were set up to manage this. They are called Regional Internet Registries, or RIRs. There are five of them spread across the world. One is ARIN, which looks after North America. Another is APNIC, which covers Asia and the Pacific. The others handle Europe, Latin America, and Africa.

These registries are not governments, though sometimes their decisions feel as powerful as laws. They are not private companies either, though they collect fees. They are communities, and they write policies by working with their members. But those policies do not stay inside meeting rooms. They decide who gets the addresses, how many can be given, and under what rules. In other words, the accessibility of the internet in different parts of the world depends on these registries. If you wonder why your provider can expand quickly in one region but not in another, the reason often sits inside the policies written by ARIN or APNIC.

ARIN and the Distribution of IPv4 and IPv6

In North America, ARIN has been the one holding the clipboard since the 1990s. At first, it was not so difficult. There seemed to be plenty of IPv4 addresses, and people thought four billion was an endless supply. Each one needed an address. Even things like fridges and cameras started asking for addresses. Suddenly, four billion did not look like enough.

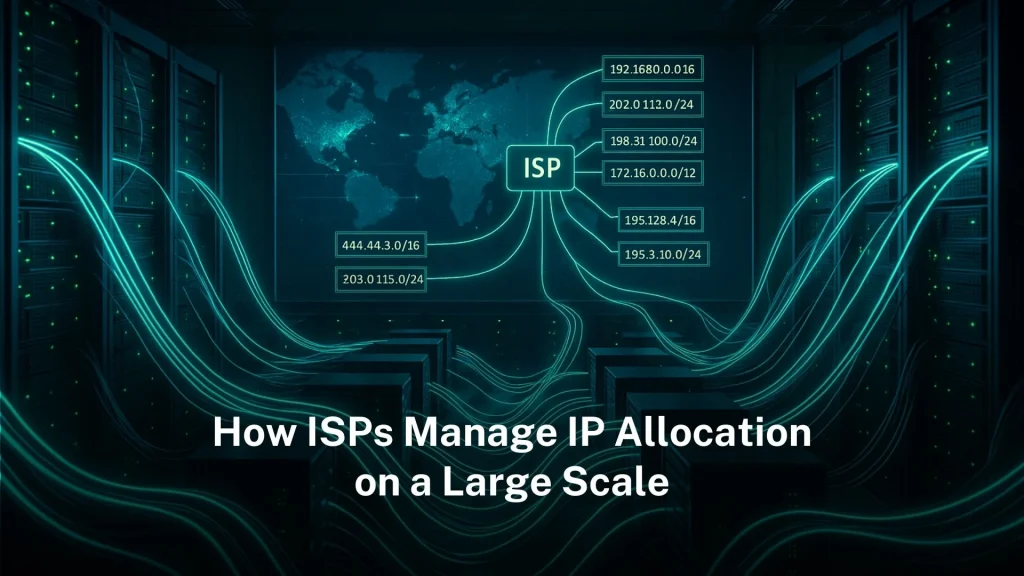

By around 2015, ARIN said the cupboard was bare. No more fresh IPv4 space was available. That announcement shook the industry. You had to either wait for scraps, or you had to enter what became known as the transfer market. Some people call it a polite word for trading. One organisation that had extra space could sell or lease it to another.

The creation of this market changed everything. For a large company with a deep budget, it was manageable. They could buy tens of thousands of addresses without worry. But for a small internet service provider in a rural town in Canada, or a community network in the Caribbean, the price was too high. Accessibility stopped being about whether fibre was laid in the street. It became about whether you could afford the digital number that let your customer even appear on the global internet.

ARIN also had to look toward IPv6, the bigger system with practically unlimited addresses. It promoted IPv6 through training, workshops, and policy nudges. Universities and some government networks moved quickly, because they had the resources. But smaller players lagged. Equipment costs money. Staff training takes time. So even though IPv6 is the solution, it has not arrived everywhere equally.

That left ARIN in a difficult position. On one hand, it had to keep recycling IPv4, approving transfers, and making sure the old system did not collapse. On the other, it had to keep pushing everyone to adopt IPv6. These two missions are not easy to balance. Be too strict with IPv4, and you punish those who cannot yet move. Be too gentle, and you remove the pressure to change. Every tweak in ARIN’s policy has a direct effect on how easy or hard it is for people in North America to get online, expand services, or innovate.

The people who feel these rules most strongly are not the big cloud providers or telecom giants. They always find a way. The impact is heavier on small ISPs, schools, libraries, and community projects. They operate on thin budgets. If ARIN’s policies make addresses scarce or expensive, their users suffer. That is why ARIN’s decisions about IPv4 and IPv6 are not abstract. They show up in the speed of someone’s connection in a rural school, or in whether a start-up can launch its service without delay.

APNIC and the Challenges of Asia Pacific

When you shift your view from North America to Asia Pacific, the picture changes completely. The scale is massive, the diversity is extreme, and the pace of growth has been far more uneven. APNIC, the registry for this region, has had to face problems that were much more complicated than what ARIN saw.

In the early days, you could see how patchy the growth was. Internet cafés were everywhere in the cities, full of teenagers playing games, but rural towns sometimes had just one shared satellite link. They were not waiting politely in line; they were jumping all at once. APNIC had to manage a flood of requests for addresses from providers that were growing at unbelievable speed.

By 2011, APNIC hit the same wall as ARIN. IPv4 was gone. They had to switch to a strict final-phase policy, which meant handing out only tiny pieces of space to new members. For old companies that already held big blocks, life went on almost normally. But for the newcomers, it was like trying to run a highway with only one lane open. The unfairness was clear, though it was not deliberate. It was simply the side effect of being late to the party.

The lack of IPv4 created odd solutions. Many providers turned to carrier-grade NAT, which forces many customers to share the same public IP. This trick kept the internet alive, but it was never smooth. Gamers in Vietnam complained they could not connect properly. Small businesses in Indonesia found it hard to host their own websites. Even a basic video call could fail because of the way traffic was squeezed through these systems. These were not just technical headaches. They directly shaped how people in Asia Pacific experienced the internet day to day.

APNIC pushed very hard for IPv6 adoption. Training workshops were held from India to the Pacific Islands, with engineers being taught how to configure routers and servers. But adoption never moved at the same pace everywhere. Singapore universities could roll out IPv6 across entire campuses. The diversity of the region also made policymaking much harder. ARIN deals mostly with countries of similar economic level. APNIC has to deal with everything from high-tech economies to very poor ones. A rule that seems fair in Seoul might be impossible in Vanuatu. If you favour the established networks, you hold back the small ones. If you favour the new entrants, you risk breaking the stability of the larger systems. Either way, someone feels left behind.

Businesses were also shaped by these rules. A start-up in India trying to launch a new platform might hit a wall because it could not get enough addresses. A telecom in Australia could simply buy what it needed on the transfer market. APNIC allowed transfers like ARIN, but the reality was harsh: money decided who moved forward and who did not. This created a gap not only between countries but also between companies inside the same region.

Even today, you can see the contrast. In Tokyo, students stream classes and never think about IP addresses at all. This is why APNIC’s policies have such a visible effect on accessibility. They are not abstract debates held in air-conditioned meeting rooms. They are rules that change how easily millions of people can get online, and how smoothly their experience will be once they are there.

ARIN and the Distribution of IPv4 and IPv6

When people first started building networks in North America, addresses were given out almost freely. It was a time when nobody thought they could run out. ARIN later stepped in and began to set rules, because by the late 1990s the growth of the internet was too fast. A single company could not just ask for millions of numbers without checks anymore. That change was important, because it meant access became more organised, though sometimes also slower.

By the time smartphones became common, the older IPv4 system was already running short. ARIN announced years ago that it had basically used up the last blocks. For anyone needing fresh IPv4, the only real options were to wait for small returns, to lease from others, or to buy in the transfer market. I remember reading that even small internet providers in places like rural Canada had to look for brokers to get extra addresses. In other words, the shortage made access unequal. Big companies could afford to buy; small ones often could not.

ARIN has been pushing IPv6 as the real answer. IPv6 has such a large pool that it feels unlimited compared to IPv4. But not everyone wants to switch. Some organisations hold on to IPv4 because older systems still rely on it. So ARIN’s policies matter here: they encourage, sometimes even pressure, people to adopt IPv6. They also set up training, guides, and community meetings to explain how to move. Even so, the speed of change is uneven. A university network may upgrade quickly, but a small ISP in Texas may still struggle.

The gap between IPv4 exhaustion and IPv6 adoption has created a kind of middle ground where policy is as important as technology.

FAQ

1. What are ARIN and APNIC?

Think of them as the traffic cops of the internet. ARIN handles IP addresses in North America, APNIC does the same across Asia-Pacific. They don’t own the internet, but without them keeping track, addresses would be a mess—like trying to deliver letters when three houses share the same number.

2. Why did IPv4 addresses run out?

Honestly, it’s because nobody planned far enough ahead. Back in the ’80s, 4.3 billion sounded like more than enough. Who would’ve guessed every phone, laptop, security camera, and even fridges would demand their own address? Once all those devices showed up, the so-called “endless” pool was gone in a blink.

3. Who struggles most with this shortage?

Smaller players, hands down. A giant tech company can just buy what it needs. But if you’re a local ISP, a school, or a community project, those prices hurt. For them, getting more addresses isn’t just tricky—it can be the thing that stops growth altogether.

4. Why hasn’t everyone moved to IPv6 yet?

Because switching over isn’t just flipping a switch. It costs money—new routers, updated software—and it takes people who actually know how to run it. Universities and big providers usually manage fine. But the smaller folks often hold off, not because they don’t want to, but because they simply can’t afford the move yet.

5. How does this affect me, personally?

More than you’d think. The rules these registries make decide whether your ISP can add more customers, whether your Zoom call glitches, or if your favorite online game feels laggy. Even small businesses hosting their own sites can be blocked by the shortage. What looks like “policy stuff” on paper ends up shaping your everyday internet experience.

Leave a Reply